THE PRESERVATION OF HISTORIC BRIDGES

(paper prepared for the 8th

Historic Bridge Conference – Columbus ,Ohio – April 2008)

By Allan King Sloan

Thanks to enthusiastic supporters of historic bridge

preservation, there is an emerging awareness of the value of saving old bridges

on the part of citizens and communities all over the country. While not designed

and built to serve the needs of modern traffic, many of these structures

continue to provide useful service and are recognized as amenities rather than

problems or hazards to the communities in which they are located. Many of these

old bridges may be an integral part of local history or may be historic in terms

of their design and engineering characteristics, or both. Efforts to preserve

them has not been easy and, indeed, most of the iron and steel bridges in the

country built in the great period of economic growth and expansion after the

Civil War have long since disappeared. However, there are some interesting

examples of successful efforts at preservation which are worthy of mention and

possible emulation.

This paper will focus on the efforts to preserve bridges

built by the King Bridge Company of Cleveland, Ohio. It was founded by my

great-great grandfather, Zenas King in 1858, and later run by my great

grandfather, James A. King and his younger brother, Harry Wheelock King, after

Zenas died in 1892. By the late 1890s the company claimed to have built over

10,000 bridges all over North America. The company started building simple

wrought-iron bowstring bridges in the 1860s and 70s, then went on to build

standard trusses and a variety of movable bridges later on. They became a

specialist in cantilever bridges and even built a notable suspension bridge in

St. Louis. By the turn of the century, they had built a number of bascule

bridges, trestles, and scores of solid beam girders for the railroads. During

the six decades the company was in business, it experienced vast changes in the

technology and business operations of the independent bridge builders and by the

early 1920s, its functions had been taken over by the big steel companies,

highway departments, and large civil engineering firms, some of which were “spun

out” of the company.

However, King bridges from each of these eras still

exist. Over the past few years a number have been preserved. Some have been

fixed up to continue to serve vehicular traffic; some have had traffic removed

and are now used as key elements of parks and other local amenities; some have

been physically removed to a new location to provide a new and different

function; some bridges built for the railroads now serve as features of hiking

and biking trails; and some historic bridges have been carefully maintained to

serve traffic as well as to represent the engineering and design concepts of

earlier bridge-building art.

In each of these cases, a particular dynamic of

socio-political forces have come into play that have made the project

successful. While the technical and engineering solutions to preserving old

bridges are often relatively easy and straightforward, the “politics” of

preservation is often more complicated. Yet it is the essential ingredient in a

successful preservation program. By far the easiest course for the owner of most

old bridges be it a town, county or state highway department (or a railroad

company) is to remove them when no longer able to carry modern traffic. The

tougher decision is to preserve them which may involve safety and liability

issues as well as pressure to “modernize”. The following are the stories of some

old bridges that have successfully dodged extinction and have found new life.

SCENARIO #1 –FIX-UP INSTEAD OF REPLACEMENT

There are some communities in which the local highway

authorities, with the strong support of the affected community, decided to fix

up old bridges to continue to carry normal traffic instead of replacing them.

While this is generally a rare occurrence, there are three recent examples that

buck the trend.

In Hopewell Township, New Jersey, the oldest bridges in

this suburban community in Mercer County (near Princeton and Trenton) are two

King through trusses which “history-conscious” local citizens wanted to keep

operating instead of replacing with modern structures.

The Bear Tavern Road Bridge (1)

built in 1882 is a Pratt truss that carries a

relatively high volume of auto traffic for an old bridge but has remained in

good enough shape for the Mercer County Highway Department to reinforce

abutments and replace the stringers and flooring to keep it in operation. The

Mine Road Bridge built in 1885 is the other Pratt truss that still

carries vehicular traffic and has needed little structural alteration over the

years. Both bridges have earned the affection of the local citizenry and have

been the subject of study by local school children interested in their

preservation. Given their status in the community, it was easy for the Mercer

County highway engineers to justify their rehabilitation instead of replacement

as the best solution.

(1)

The Bear Tavern Road Bridge during and after rehabilitation

In Marion, Virginia, an 85-foot Pratt through

truss, called Happy’s Bridge (2) built by the King Bridge Company in1885,

connects a road intersecting Main Street in downtown across a small river with a

riverside park and some other public buildings. The local community decided it

wanted to keep rather than replace the old bridge and in 2005 it was

rehabilitated as a joint venture of Virginia DOT and the Town of Marion for

total project costs of $481,088, 80% funded by the state through Federal T-21

grant money and 20% by the town. The reopening of the bridge was a cause for a

community celebration that provided an excuse for owners of old wagons and cars

to proudly parade their vehicles.

(2) Happy’s Bridge before and after restoration

In Lewis and Clark County, Montana, the

Dearborn River High Bridge (3) is a unique four span 160 foot deck truss

listed on the National Register of Historic places. It was built by the King

Bridge Company in 1897. Located in a spectacular site on a remote county road in

the foothills of the Rockies, it is not particularly well known to local

inhabitants who would have little reason to use it. However, the historian of

the Montana Department of Transportation, Jon Axline, was able to persuade his

peers that this historic structure was well worth preserving, and in 2003 the

department contracted with HDR Engineering to do the repair of the truss

components, piers, decking and abutments with spectacular results.

(3) The Dearborn River deck truss restored

The more likely scenario to preserving an old bridge

is by insuring that the structure is taken out of harm’s way; that is removing

it from an active of vehicular traffic system This can occur either if the

location of the bridge lends itself for a non-traffic use as part of an

“amenity” or if it can be relocated to a “safe” location. There are a number of

recent examples of each of these situations.

SCENARIO #2 – USING THE BRIDGE IN AN “AMENITY PACKAGE”

A number of communities have used their old bridges in

projects to create an “amenity package.” This may include reducing or

eliminating their use for vehicular traffic, turning them into pedestrian

facilities, or integrating them into parks or public spaces. Three of these

have been undertaken recently in upstate New York.

In Chili Mills, Monroe County, the Stuart Road Bridge (4)

is 74-foot bowstring sitting adjacent to a picturesque mill pond surrounded

by the original buildings carefully tended to for years by the Wilcox family,

the owners of the mill site. It has been known to the locals as the “Squire

Whipple” bridge in honor of the inventor of this bowstring design and was built

by the King Bridge Company in 1877. It has played a role in an annual village

celebration of “the Squire” in full period dress. After persistent efforts of

the Wilcox family and their friends, the Monroe County Department of

Transportation undertook the rehabilitation of the bridge in 2002 using their

own manpower and at minimal cost.

(4) The Stuart Road Bowstring restored

In Newfield, Tompkins County, the Beech Road Bridge

(5) is a 54-foot Zenas King patented Bowstring and one of two historic

bridges in this village near Ithaca. The covered bridge in the center of the

village has long been celebrated. The bowstring built in 1873 had not been

subject to the same esteem until recently. Long closed to vehicular traffic, the

bowstring plays and important role as a pedestrian crossing of a deep ravine,

particularly for school children. For years the responsibly for the upkeep of

the bridge was debated between village and county officials until a local ad hoc

citizens group headed by local citizen, Karen Van Etten, organized the effort to

rehabilitate the structure. After years of lobbying and fund raising, the

bowstring was and rehabilitated in 2004 and the grand reopening covered by the

New York Times. The project costs of $77,000 were contributed by the

county with funding from Historic Ithaca, the local historic preservation

organization. As a follow up, a local land owner has contributed property next

to the bridge for a new village park.

(5) The Beach Road Bowstring before and after restoration

In Canton, St. Lawrence County, the Grasse River

Bowstring (6) is a long-abandoned 1870-vintage King tubular arch

bowstring across the Grasse River near the center of this college town. It has

the potential to provide pedestrian access to an island in the middle of the

river which a local preservation group, the Grasse River Heritage Area

Development Corporation, is creating a park celebrating the industrial history

of the town. Rehabilitation will allow the bridge to be used as pedestrian

access to river islands once populated by mills. The bridge and island

restoration was funded by a grant of $177.353 from New York State and $110,000

raised by the Development Corporation from local citizens. Barton and Loguidice

Engineering of Syracuse managed the project starting with the rehabilitation of

the bowstring completed in November, 2007.

(6) The Grasse River Bowstring rehabilitation underway

In River Edge, Bergen County, New Jersey, a

110-foot Pratt swing bridge was built by the King Bridge Company 1889 and known

ironically as “New Bridge” (7). It is listed on the National Register of

Historic Places. Owned by the county, it was rehabilitated some years ago to

serve as a pedestrian crossing over the Hackensack River. It connects to the

headquarters of the Bergen County Historical Society at Steuben House, an

important historical site dating from the War for Independence to a town park on

the other side of the river. Although now stationary, the mechanical elements of

the turntable used to move the bridge (by hand) are still in place.

(7) The New Bridge at River Edge before and after

restoration

In Unadilla, New York, a two-span Pratt

through truss bridge crosses the Susquehanna River in the hamlet of Wellsbridge

(8), located adjacent to State Route 44. When the bridge became unsuitable for

modern traffic, state highway officials, in their wisdom, decided to leave the

old bridge in place and build the new bridge in a parallel alignment. The result

is an interesting combination of old and new structures with the King, built

1886 trusses providing a pedestrian crossing and viewpoint for river watching.

For “safety” reasons, the old bridge’s capacity has been restricted to only

eight people at a time. In the view of some local bridge enthusiasts, this

prevents its use as a place to watch rafting and other river sports, a major

attraction in the area.

(8) The old spans at Wellsbridge beside the replacement

bridge

SCENARIO #3 – MOVING TO A NEW SITE

A number of interesting examples of old bridges were

moved to new locations to insure their preservation. These efforts pose a number

of logistical problems and sometimes require heroic efforts, but the results are

often spectacular.

In Jones County, Iowa, the Hale Bridge (9)

a Zenas King patent bowstring comprising two 80-foot spans and one 100-foot span

was built in 1879 and listed on the National Register and in HAER. On

Wednesday, March 8, 2006, Iowa Army National Guard Chinook helicopters moved the

rehabilitated trusses from the staging site to their new home at the

Wapsipinnicon State Park in Anamosa This landmark event drew an excited crowd of

Iowans and was covered by the History Channel’s new series MEGA MOVERS that was

aired on June 27, 2006, as well as the New York Times and the local

press. The restoration was completed in late summer of 2006 and the bridge now

serves as the new entrance to a hiking and biking trail in the park. The Jones

County Historical Society headed by Rose Rohr took the lead in organizing and

orchestrating this highly successful multi-year bridge preservation effort in

which a large number of state and local governmental agencies were involved.

(9)The spectacular relocation of the Hale Bridge,

Anamosa, Iowa

Ashtabula County in northeastern Ohio is known for

its historic covered and iron bridges. The Mill Creek Road Bridge (10) is

a 104-foot Pratt Through Truss built by the King Bridge Company in 1897

that was rehabilitated and relocated from Mill Creek Road to the Western Reserve

Greenway Trail. The project was supervised by the Ashtabula County engineer’s

office and Union Industrial Co. of Ashtabula was the contractor. The project

cost included $81,311 for removal and disassembly and $ 209,570 for structural

rehabilitation for a total of $291000. The Grand River Partnership, a private

group devoted to the protection and enhancement of the rivers in northeastern

Ohio, hopes to protect a similar bridge on Johnson Road by including it in a

scenic easement being acquired on adjacent land along the river.

(10) The Relocated Mill Creek Bridge, Ashtabula County

In Northport, Alabama, the Black Warrior

(Espy) Bridge (11) is a single 203-foot bowstring built in 1882 as part

of a three span bridge across the river that was removed many years ago to a

remote location in the county. It is the oldest iron bridge in the state. Now it

is being relocated back to near its original location on the levee system in

Northport as part of a walking trail system. Funds are being provided by the

Alabama DOT using Federal T-21 money with 20% to be provided by the City of

Northport. This effort has required years of hard work by the Friends of

Historic Northport, a local citizens group led by

Ken Willis and others which had to develop the concept for relocating the

structure, raise money, and persuade the public authorities to undertake the

project. Plans for the disassembly and moving of the bridge have been completed

and the project is finally underway at an estimated cost of about $115,000.

The civil engineering department of the University of Alabama is also assisting

in the program.

(11)The Black Warrior Bridge awaiting relocation

While moving an old bridge to a new location requires a

substantial logistical effort, local acceptance, and cost, there are other

situations in which an old structure abandoned for its original use can still

serve a new function. This is particularly true of railroad bridges that have

been left standing after the rail services have been terminated and current

owners are willing to change the function of the structure.

SCENARIO #4 – CREATIVE USE OF OLD RAILROAD STRUCTURES

As the importance of nation’s railroads have faded, there

are a number of abandoned or underutilized bridges of various types that have

been put to new use, particularly as part of “rails to trails” and similar

programs. A number of old King bridges have been in this situation.

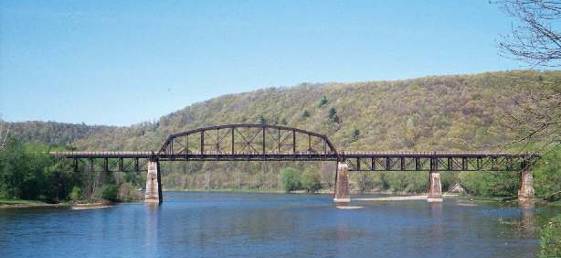

In Venango County, Pennsylvania, the Belmar Bridge

(12) is a 1,361-foot long structure built for the Jamestown, Franklin and

Clearfield Railroad in 1906 by the King Bridge Company under a subcontract to

the Thomas McNally Company of Pittsburgh. The bridge is now part of the East

Sandy Creek Bicycle Trail operated by the Allegheny Valley Trails Association

and offers panoramic views of the Allegheny River and the surroundings.

(12) The Belmar Bridge across the Allegheny River

There are other examples of rail to trail

conversions, including the Tunnel Hill State Trail in Southern Illinois between

Harrisburg and Karnak. Five King bridges originally built in 1912 for the Old

Big Four Railroad are now used by hikers and bikers through one of the most

picturesque areas of the state. The trail itself recognizes a variety of

railroad bridge engineering.

In Ulster County, New York, the King Bridge

Company built a 925-foot trestle across Esopus Creek in Rosendale for the

Wallkill Valley Railroad in 1895, called the Rosendale Viaduct (13). When

all service on this line was abandoned in 1976, a local railroad enthusiast and

entrepreneur, John Rahl, used his research of state law regarding railroad

abandonment to purchase the structure and eleven miles of adjacent rail bed for

a minimal cost and converted the viaduct for pedestrian use as part of the

Wallkill Valley Rail Trail.

The bridge is in good condition and has been equipped with wooden

planking and railings so that people can walk out onto the bridge to take in the

spectacular views across the valley and the Hudson River beyond. The viaduct is

considered to be unique landmark and an asset to the village of Rosendale.

(13)The Rosendale Viaduct pictured in an1890s King

Bridge Co. catalogue and today

In St. Francisville, Illinois, the Wabash Cannonball

Bridge (14) built in 1906 once carried the famous Wabash Cannon Ball

train across the Wabash River. When the railroad abandoned the line, the bridge

was purchased by a local farmer to haul his produce across the river but is now

owned and maintained by the town of St. Francisville as an historic artifact.

Its one lane is still open for trans-river vehicular traffic.

(14) The Wabash Cannonball Bridge today

Two imposing bridges built for the New York Central

Railroad on the Buffalo to Rochester line by the King Bridge Company are still

standing. The first is a 124-foot Deck Truss Bridge (15) across the New

York State Barge (Erie) Canal in Lockport, near Buffalo. It was built in

1902 and is still used today for occasional passenger excursion and local

freight trains. Tom Callahan owns the old water works facilities adjacent to the

canal for development as an exhibition of historic hydraulic technology. He is

leading efforts to restore the footbridge along side the track, traditionally

one of the best places to view the five step locks of the canal, one of the

areas important tourist attractions. The second is the 304-foot Hojack Swing

Bridge (16) near the mouth of the Genesee River in Rochester, built in 1905 and

abandoned in 1993. Despite the valiant multi-year effort of a group of local

preservationists headed by Richard Margolis, the U.S. Coast Guard has ordered

the removal of the bridge, as it is no longer used for transportation and is a

“hindrance to navigation”. Public officials in Rochester have shown remarkable

indifference to the preservation of this fine example of swing bridge

technology. Since the costs to the owner (CONRAIL) of its removal will be

substantial and the impact on the river of the removal of the turntable

substructure unknown, the bridge is still in place.

(15) The Deck Truss at Lockport

(16) The Hojack Swing Bridge at Rochester

Fortunately, there are communities that appreciate the

value of their old bridges and have taken measures to insure their protection

and continued use, even if extensive maintenance and rebuilding is required.

Cleveland, the home of the King Bridge Company, and New York City, which was in

effect created and developed by its historic bridges. Two King built bridges

represent the best of this tradition.

SCENARIO #5 – CARE AND MAINTENANCE OF IMPORTANT BRIDGES

In Cleveland, Ohio, the Center Street Swing Bridge

(17) is a famous bob-tailed swing bridge built in 1901. It is now part of

the Cleveland’s impressive inventory of historic bridges, three of which were

built by the King Bridge Company. It still functions as a vehicular crossing of

the Cuyahoga River providing access to the entertainment complex in the Cuyahoga

River Flats. It is historically important, both for its design and role as a

working swing bridge. It is often described in historic bridge literature and is

kept in operation through the enlightened maintenance program of the city’s

bridge engineering department.

(17) Cleveland’s Center Street Swing Bridge today

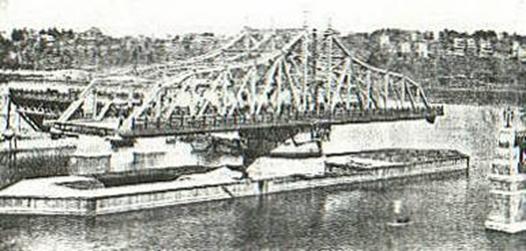

In New York City, the University Heights Swing

Bridge (18) crossing the Harlem River at 207th Street in Manhattan to

West Fordham Road in the Bronx, began life as a swing bridge across the Harlem

Ship Canal at Knightsbridge Road in 1895 and was featured in the King Bridge

Company catalogues of that era. To make room for a larger bridge that would

carry the Broadway subway line across the canal, this bridge was loaded on

barges and floated to its present site in 1905 and reconstructed with new piers

and approaches. The bridge was considered to be a significant engineering and

architectural structure was awarded landmark status in 1983 by the City’s

Landmark Preservation Commission. The bridge now serves both vehicular and

pedestrian traffic moving between the Inwood Community in Upper Manhattan and

the Fordham University area in the Bronx, and a visit to the bridge is well

worth the experience.

(18) The Harlem Ship Canal Swing Bridge pictured in the King Bridge

Company Catalogue

(18) The University Heights Bridge today

SUCCESS FACTORS IN OLD BRIDGE PRESERVATION

These examples of preservation efforts each represent one

or a variety of factors that have been key to a successful outcome. While these

examples are selective and do not necessarily represent the universe of

successful programs, they do demonstrate the main characteristics that appear to

be essential. These are:

1.

THE NEED FOR A “CHAMPION”

It is clear that these preservation efforts would never

have been mounted unless there was a “champion” leading the charge. This

champion might be a local historical or environmental group, a dedicated

individual with lots of energy, patience and fortitude, an enlightened local

highway department, state DOT, or an engineering firm willing to undertake

projects with often modest funding. These champions must be willing to work hard

to understand the “politics” of the situation, organize community support, find

funding sources, pull strings, and make sure the process works. Without such a

champion, most efforts will fail.

2.

AN APPROPRIATE “SETTING” AND “ENVIRONMENT”

There needs to be the realistic opportunity for the old

bridge to be put out of harms way (ie, not put in the position of continually

having to carry high volumes of modern traffic, unless extensively rebuilt).

Public parks or reservations, riverside conservation areas, hiking-biking trails

give the old bridge a chance to become a local “amenity” rather than a traffic

bottleneck, a danger point, or an eyesore. If the bridge is still to be used for

traffic, restraints and restrictions have to be honored, particularly by the

drivers of large and heavy vehicles.

3.

A “SYMPATHETIC AND SUPPORTIVE” LOCAL COMMUNITY

Local village, town, city or county officials must be

supportive rather than hostile to the preservation effort. They must recognize

the potential role the bridge can play in enhancing the community’s image and in

celebrating its history The indifference or hostility of local, county or state

highway officials can be a serious impediment to old bridge preservation It is

often the role of the “champion” to lobby for this support with whatever methods

of persuasion are available..

4.

FUNDS FOR PRESERVATION

In the preservation efforts noted above, the level of

funding required for preservation have ranged from minimal (Chili Mills) to

moderate (Mercer County’s annual maintenance program for the Hopewell bridges)

to major (for the large relocation efforts ( in Iowa). Funds have come from a

variety of sources with Federal Transportation Act T-21 funds playing a key role

in large projects. Local taxes and funds raised by private non-profit

organizations like historical and environmental groups are very important

catalysts for obtaining public funding. Bundling old bridge preservation funding

in with larger park development programs (Canton, New York) is often a good way

to get adequate funding levels. However, unless those officials who control

major funding sources are brought on board, the preservation efforts will be

hard to achieve.

5.

THE HISTORIC BRIDGE FRATERNITY HAS AN IMPORTANT ROLE TO PLAY

Putting the old bridge into its appropriate historical

context is most often a key factor in justifying efforts to preserve it. The

members of the historic bridge fraternity are the holders and purveyors of this

information. Federally mandated state-wide historic bridge inventories are often

a good starting point for a particular preservation program, but being included

on an historic bridge list does not guarantee survival. The growing number of

bridge preservationists are now connected through the internet. Websites created

by Nathan Holth, James Baughn, Daniel Alward and others are extremely important

in flashing the warning signals when an old bridge is in danger. Local champions

need to be supported by the historic bridge fraternity in their efforts to

justify preservation by providing “bridge history” to supplement to role of the

bridge in “local history”. Both types of justification are usually needed for

success.

In the successful examples cited above all five of these

factors were favorable. Where one or more of these factors are missing, the

efforts are most often frustrated.

Author’s note:

In preparing this paper, the preservation examples

selected are those in which I have some direct personal knowledge, including

visits. Thus they are heavily concentrated in New York, Ohio, and other eastern

states which are near my home base. There are many other examples that should be

included in any complete list of successful preservation efforts, particularly

in Texas, (The Faust Street, Moore’s Crossing, Alton in Denton, and the Bullman

Bowstring bridges) Indiana (The Boner Bowstring, Madison, and Atterbury

bridges), Michigan (the bridges in Allegan and Belle Isle), Kentucky (the

Singing Bridge in Frankfurt and the Bowling Green Bowstring), Minnesota, (the

Merriam Street Bridge), Wyoming, (the Fort Laramie Army Bridge), as well as

Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Kansas, Arkansas, and even Nova Scotia. Historic

bridge preservation programs in many of the Midwestern states have very strong

backing from State DOTs. This has been important in the number of successful

programs implemented there.

Photo Credits;

1.

The Bear Tavern Road Bridge – Charlotte Pashley and A.K.Sloan

2.

Happy’s Bridge –A.K. Sloan and S.Wilson – Thompson&Litton

3.

Dearborn River Bridge – Montana State Department of Transportation

4.

The Stuart Road Bowstring - A.K.Sloan and J. Stewart

5.

The Beech Road Bowstring – A.K.Sloan and N.Holth

6.

The Grasse River Bowstring –J.Stewart and Grasse River Heritage

7.

The New Bridge at River Edge – Bergen County Historical Society and A.K.

Sloan

8.

Old spans at Wellsbridge –J.Stewart and A.K.Sloan

9.

The Hale Bridge relocation – A.K.Sloan, Cedar Rapids Gazette, and Jones

County Historical Commission

10.

Relocated Mill Creek Bridge – A.K.Sloan

11.

The Black Warrior Bridge – K.Willis

12.

The Belmar Bridge – D. Alward – Venangoil website

13.

The Rosendale Viaduct – A.K. Sloan

14.

The Wabash Cannonball Bridge – P. Kennedy

15.

Deck Truss at Lockport – A.K.Sloan

16.

The Hojack Swing Bridge – A.K.Sloan

17.

Center Street Swing Bridge – W.Vermes

18.

The University Heights Bridge – A.K.Sloan